Can I retire now?” used to be something you’d expect a 55-year-old to ask. But now, young, high-net worth individuals, in their 40s or even younger, might be thinking about the same thing.

Here’s the challenge: Assumptions used in traditional retirement planning don’t apply to “extreme early retirement.” 40-somethings might think they can retire now if they invest 25 times their annual spending, which correlates to the commonly cited “4% withdrawal” rule. Research, though, suggests the number is closer to 36 times annual spending.

The ramifications of research reach far beyond 40-year-olds looking to hang it up early. Most people will likely need to save considerably more than they thought for a secure retirement. The analysis also calls into question assumptions used in retirement planning, including the oft-quoted “4% withdrawal rule.”

Why People Think They Can Retire at 40

Typical retirement math can be dangerous for clients who want to call it quits extremely early. In simple terms, the math only works if a series of historic assumptions hold true. The 25-times rule is the mathematical inverse to the idea a retiree can withdraw 4% of a portfolio’s original value and be reasonably sure they won’t run out of money. This analysis is derived from historical simulations in a seminal research paper titled, “Determining Withdrawal Rates Using Historical Data” by William Bengen. For a 39-year-old worker who requires $100,000 a year to pay annual expenses, a nest egg of 25 times that, or $2.5 million, would be their number before taxes and assuming 3% annual inflation.

Saving 25 times annual spending would be an onerous task for most 40-year-olds, but a combination of a high income, inheritance or frugal living could make it doable.

Consider Our Three-Factor Extreme Early Retirement Model

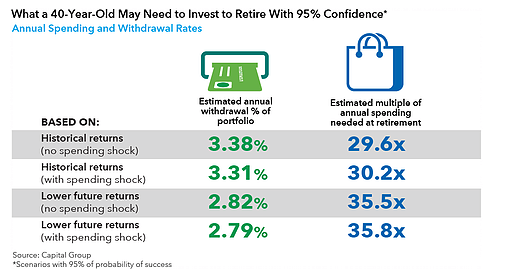

Traditional assumptions don’t hold up over substantially longer periods – the odds a 40-year-old retiree would face a negative expense or market event are much greater. A 40-year-old looking for $100,000 in annual income would need a starting investment of $3.6 million going into retirement to be reasonably confident, subject to certain assumptions, they won’t run out of money. (Over 40% more than traditional assumptions would imply.) Keep in mind, too, the sum needed would be after-tax dollars, which needs to be factored in if some of the money is saved in a pre-tax retirement vehicle such as a 401(k).

Why does our conclusion differ so much from the commonly held rules of thumb? Traditional retirement planning severely underestimates three mains risks that need to be adjusted for:

1. Longer time horizons following retirement raise reliance on market returns.

The original 4% withdrawal rule was based on the assumption of a 30-year retirement with a life expectancy of 95. But that math must be reworked for clients adding 25 years of retirement to support. Rocky returns, especially early in a lengthy retirement plan, can be devastating. “If you don’t account for (poor returns early in retirement) you could find a bad run, especially in your 40s, could leave you way short of what you’ll need to get to age 95,” says Brett Hammond, Client Analytics Research Leader at Capital Group. To adjust for this risk, we looked at a Monte Carlo analysis simulating 10,000 possible market scenarios of a portfolio comprised of 60% large U.S. equities and 40% intermediate blended bonds over retirements of various lengths. We used this to estimate the savings required to have 95% confidence of having an ending value greater than $0 in the final year of simulation before age 95.

2. Market returns going forward could be lackluster compared with past results.

Some investment professionals expect future returns to be lower than they’ve been in the past since interest rates and economic growth rates now are also below what they have been historically. “Instead of 4%, if there’s a new normal, the withdrawal rate is less than that,” says Sunder Ramkumar, senior vice president of Capital Group’s Client Analytics group. This risk is more significant the earlier a client retires, Ramkumar says, since investment returns become that much more important.

To adjust for those lower forward assumed returns, we used an investment advisor survey of long-term market returns estimates conducted by Horizon Actuarial Services. These estimates point to an average annual market return of 7.59% from U.S. large equities, well below the more than 9% historical average annual return of the market.

3. Young retirees face extra years of the risk of unexpected spending shocks.

A person who quits work at 40 years old faces 55 years at risk of an unexpectedly large emergency cost. Think a major health issue or a significant home repair. This is a real concern: 38% of retirees experienced a spending shock of 25% or more during retirement, according to a study of 733 retirees in August 2015 by the Society of Actuaries.

To adjust for these costs, we factored in a 20% unexpected hit to a client’s portfolio at age 75. The results are notable.

A Chart to Share With Your 40-Year-Old Clients

Putting these three factors together creates a more realistic forecast, like the one in the chart below. This shows you what your 40-year-old client could be looking at in savings and investing needs – and how the three adjustment factors affect their plans.+

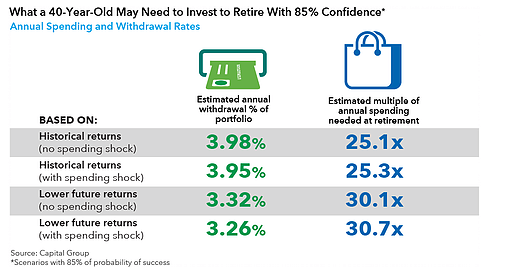

Some 40-year-olds might think they’re willing to take a bit more risk that their plan might fail by accepting a lower probability of success. They figure they can always return to the workforce. But even after adjusting the analysis to allow for greater chances of retirement plan failure, the numbers are still much more restrictive than traditional plans would suggest.

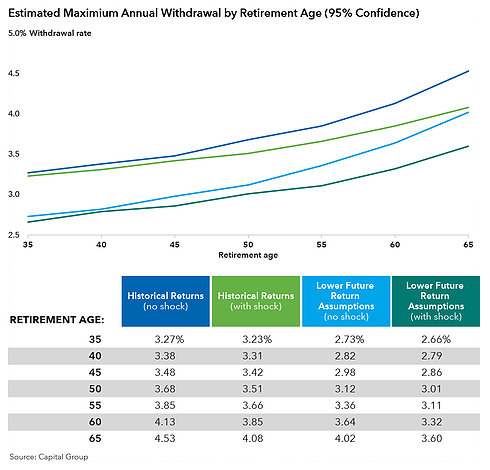

Going Beyond the 40-Year Old

It’s easy to discount the early retirement dreams of our 40-year-old, chalk it up to the delusions of youth. But our analysis has meaning for all retirees who want to prepare for realistic retirement expectations, no matter their age. While commonly cited as “safe,” 4% withdrawal rates may be overly optimistic even for clients who retire at more traditional ages.

Below is a table showing the withdrawal rate for people based on a variety of ages. Interestingly, a 4% withdrawal rate appears aggressive even for a 65-year-old using more conservative future market returns data and factoring in unexpected financial hits.

Certainly, there are important caveats in individual situations that require deep consideration, as people have their own unique circumstance. It’s possible that spending needs may fall as clients age.

But it would appear that many 40-year-olds who are counting on spending lots of extra time on the beach might want to remain in the workforce at least a bit longer, factor in part time work for extra income or at least beware of the various risk.

****

Analyses based on a Monte Carlo simulation, a statistical technique that provides a range of potential outcomes using a large number of scenarios based on capital market assumptions. The capital market assumptions used here are 9.34% for stock and 4.25% for bonds on a historical basis and 7.59% for stock and 4.48% for bonds on a forward basis, annualized. The allocation was rebalanced monthly. The results of the simulation are highly dependent on the assumptions used and there can be no assurance that these assumptions will prove to be accurate. Accordingly, actual results may vary significantly from the simulation results presented. Neither taxes nor fees were included in any of the scenarios. Annual spending assumes $100,000 a year to pay expenses, adjusted for 3% annual inflation. Past results are not predictive of results in future periods.