A benchmark serves a crucial role in investing. Often a market index, a benchmark typically provides a starting point for a portfolio manager to construct a portfolio and directs how that portfolio should be managed on an ongoing basis from the perspectives of both risk and return. It also allows investors to gauge the relative performance of their portfolios.

What is a benchmark?

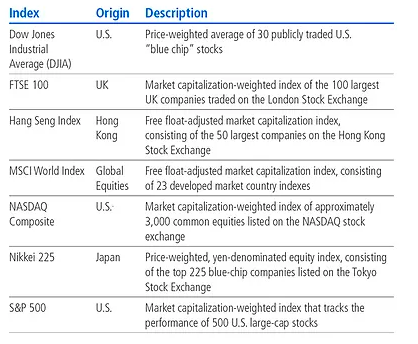

In most cases, investors choose a market index, or combination of indexes, to serve as the portfolio benchmark. An index tracks the performance of a broad asset class, such as all listed stocks, or a narrower slice of the market, such as technology company stocks. Because indexes are unmanaged, they track returns on a buy-and-hold basis and no trades are made to reallocate to securities that may be more attractive over different market cycles or market events. Indexes represent a “passive” investment approach and can provide a good benchmark against which to compare the performance of a portfolio that is actively managed. Using an index, it is possible to see how much value an active manager adds and from where, or through what investments, that value comes.

Fixed income securities do not trade on open exchanges, and bond prices are therefore less transparent. As a result, the most commonly used indexes are those created by large broker-dealers that buy and sell bonds, including Bloomberg Barclays Capital (which now also manages the indexes originally created by Lehman Brothers), Citigroup, J.P. Morgan, and BofA Merrill Lynch.

Bond firms have created dozens of indexes, providing a benchmark for virtually any bond market exposure an investor might want. New indexes are often created as investor interest grows in different types of portfolios. For example, as investor demand for emerging market debt grew, J.P. Morgan created its Emerging Markets Bond Index in 1992 to provide a benchmark for emerging market portfolios.

What are the methodologies used to create indexes?

The major index providers use specific, predetermined criteria, such as size and credit ratings, to determine which securities are included in a particular index. Index methodologies, returns and other statistics are usually available through the index publisher’s website or through news services such as Bloomberg, Morningstar or Reuters.

Instead of averaging stock or bond prices, indexes typically weight each component; the most common weighting is based on market capitalization. Companies with more equity or debt outstanding receive higher weightings and therefore have greater influence on index performance. As a result, big price swings in the stocks or bonds of the largest companies can create big price movements in an index.</div><div>How are benchmarks used to track performance?

The difference between the performance of an individual portfolio and its benchmark is known as tracking error. Typically reported as a standard deviation percentage, tracking error may be positive as well as negative. When a portfolio is actively managed, tracking error may reflect the investment choices made by the active manager in an attempt to improve performance. If the active manager is successful, tracking error is positive and the portfolio outperforms the benchmark; if not, the portfolio underperforms its benchmark.

How do I select a benchmark?

With a vast number of benchmarks to choose from, deciding which one, or which combination of indexes to use, can be difficult. Here are some key questions to answer before you choose.

What are your overall performance goals, and what is your tolerance for volatility, or risk?</div><div>Investors should evaluate their return goals and risk tolerance before selecting an index. An investor with a low risk tolerance will most likely select an index with a shorter duration or higher credit quality. An investor looking for a high return may select an index with a track record of high long-term returns, which might also exhibit performance volatility and carry the chance of negative returns over shorter time periods.</div><div>How many different types of securities do you want your portfolio manager to be able to invest in?

A benchmark should be a “good fit” for your portfolio and your investment manager in terms of the range of securities in which it can invest. A broad investment universe can potentially help increase return and reduce volatility. If the benchmark is “too narrow,” however, it may be difficult for the investment manager to make noticeable contributions to the portfolio’s overall performance through active management.

What are the risks?

With benchmarks today covering all types of assets and investment strategies, investors should carefully consider the underlying risks in a benchmark, or index, and their risk tolerance when evaluating an index. Investors should also be aware of the holdings in their portfolios compared with those in their benchmarks in order to understand why their portfolios may perform differently. All investments contain risk and may lose value.